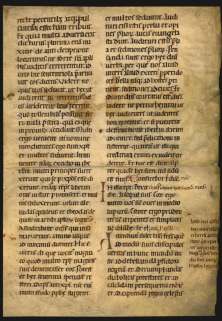

The parchment fragments talk to me.

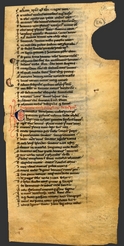

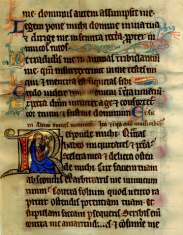

That glabrous, wrinkled surface, sprinkled with pores clogged by dust and sweat.

Those fragments exude the history that has passed through them, it is enough to just listen to them.

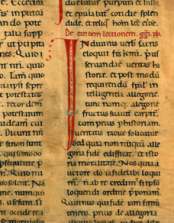

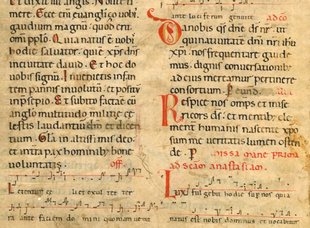

Even before reading them, they tell me of the person who wrote them, of the care that had been taken in ordering the very words and their abbreviations – because parchment is so dear.

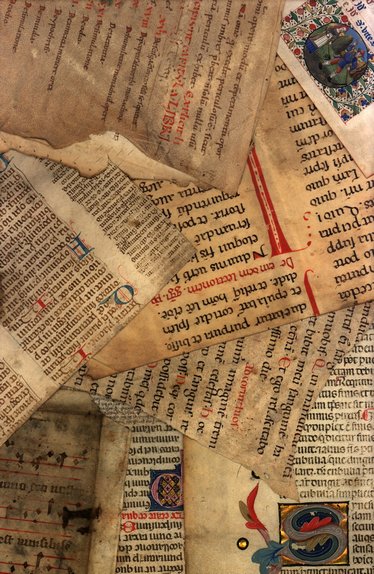

They tell me of the time when they were stored in a chest down there in the cellar, where humidity has swollen them up.

But then someone finds them and uses them again to enclose and wrap other leaves up. And the parchment once again shrinks, twists, crumples.

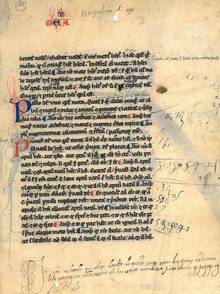

And it continues to tell me about itself, through the words annotated on its margins, in the numbers jotted down by pencil on a corner.

And in the same way as an archaeological excavation, as I go down layer after layer until I have found the virgin soil, so I read and understand the reuses of this fragment, too: when it was first cut and written, all the way up to its most recent use.

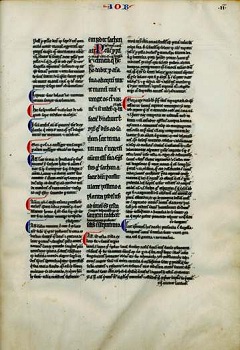

The fragmentation of the manuscript, in virtue of which we still run into each of its fragments, but not recent phenomena can be traced back at least to the fourteenth century, a period in which stacionari or cartolari - that is, the owners of the shops where they produced and recopy college textbooks - also became sellers of cards papyrus and parchment, both new and old, written, unwritten and recovered from bound books.

Furthermore, the advent of printing in the next century revolutionized the production of books, popular books and reading the new content easier thanks to the regularity of the characters, gradually marginalizing the book manuscript. Following this book authentic revolution, the monasteries - the ancient treasures of knowledge - began to sell off or transfer manuscripts when they could get the printed editions of the same texts.

In the age of humanism and the Renaissance, sheets and double sheets of parchment codes to be destroyed were reused from the era, such as binders, covers and sheets on guard, or hidden in the books as reinforcement. And so, in a manner not dissimilar to the fate of archaeological monuments reused as building quarries, also considered obsolete manuscripts were used as a material recovery.

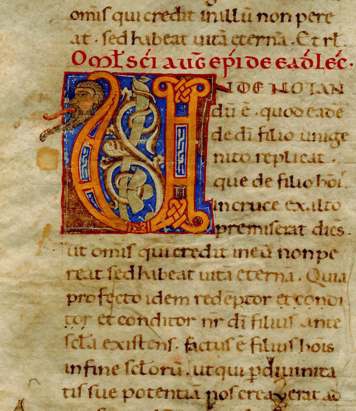

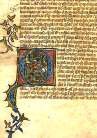

In later centuries the taste for new and contempt for the middle age and all that was heard as "gothic", including medieval manuscripts, led to a 'further dissipation of the manuscripts, antiquarian and collectible until the interest start of the eighteenth century did not give the actual destruction of raids in the codes, which were cropped miniatures and decorated initials: with a certain cruel irony, the Age of Enlightenment ended in this way to plunder the treasures of the Middle Ages with the same brutality that the intellectuals of the time attributed to the "barbarians" who plundered the remains of the ancient world.

Science in the Middle Ages

The medieval world has provided the following centuries some of the prerequisites for the birth of modern science has not only provided a large body of translations of Greek and Arabic texts (Aristotle, Plato, Avicenna), but also invented an institution, the university , which formed a specific space for the West philosophy and rational, and created a class of intellectuals, philosophers and theologians who, from within the universities themselves, have made free to live the faith with critical analysis.

The great thinkers of the Middle Ages felt strongly the significance of its ancient culture, Bernard of Chartres (1150) argued that

"We are like dwarfs on the shoulders of giants,

so that we can see more than they and things

greater distance, not by virtue of any sharpness of sight on our part,

or any phisical distinction, but because we are carried high

and raised up by theyr giant size"

This song became famous and commonly used, refers to the sum of the constitutive theory of science in the Middle Ages. The programs of study, in fact, were based on reading auctoritates or texts by authors of various antiquities which formed the basis of the individual disciplines, which were added the most acclaimed modern commentaries.

The list of textbooks university was then supplemented by glosses and summae of many professors. The basic texts of law were in Corpus Juris, Corpus Juris Civilis and Canonicis. In Bologna, these texts were commented on with the help of the glosses of doctors in Bologna, synthesized by Accursio Francis (1182- 1260) in the Ordinary Gloss.

For the doctors were referred to Hippocrates, Galen, Constantinus Africanus, the Canon of Avicenna and Averroes Colliget. The study of theology was based on two key texts: the Bible, the works of the Fathers of the Church and the book of the Sentences of Peter Lombard.

The theologians also used a purely philosophical texts, such as those of Aristotle and Arab philosophers, Aristotelian texts, however, had greater use at the Faculty of Arts (later merged with that of Medicine), who presided at the preliminary training university of the scholar, equipping the bases not only grammar and rhetoric, but also logical and philosophical, real prerequisites for access to faculty and more complex studies.